30 Years into democracy: How has South Africa's agricultural sector performed?

Introduction

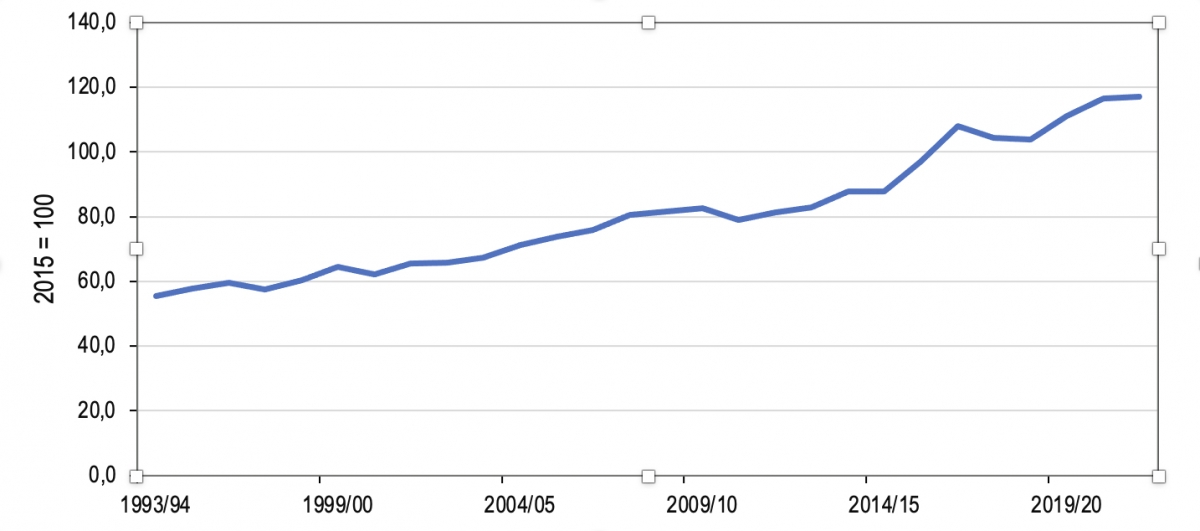

There are divergent views about the efficacy of South Africa's agricultural policies. Since 1994, the sector has grown substantially – as illustrated in Figure 1 below. Data from the Department of Agriculture, Land Reform and Rural Development show that domestic agricultural output in 2022/23 was twice as high as in 1993/94.

Whether this growth has been inclusive and transformative is a key question. But for now, it's important to emphasize the growth of the industry and the drivers of its expansion. Significantly, this expansion was not driven by a few sectors but has been widespread -- livestock, horticulture and field crops have all seen strong growth over this period.

Although the production of some crops, most notably wheat and sorghum, has declined over time, this had to do with changes in agroecological conditions and falling demand in the case of sorghum. It was not a failure of policy.

Figure 1: South Africa's agriculture's journey from 1994 (volumes of production of all agricultural subsectors)

Source: DALRRD and Agbiz Research

These higher production levels have mainly been underpinned by the adoption of new production technologies, the development of better farming skills, growing demand (locally and globally), and progressive trade policy. The private sector has played a major role in this progress.

Progressive trade policy is reflected by South Africa's standing in global agriculture. The country was the world’s 32nd largest agricultural exporter in 2022, and the only African country within the world’s top 40 largest agricultural exporters in value terms. This is according to data from Trade Map.

This was made possible by a range of trading agreements secured by the South African government over the past decades, the most important being with the African continent, Europe, the Americas, and some Asian countries. The African continent and Europe now account for about two-thirds of South Africa's agricultural exports, with Asia being another important market.

The agricultural subsectors that have benefited the most from the rise in exports are horticulture (and wine) and grains. Broadly, South Africa now exports roughly half its agricultural products in value terms. In 2022, South Africa's agricultural exports reached a record US$12,8 bn.

Aside from the exports

South Africa is now ranked 59th out of 113 countries in the Global Food Security Index, making it the most food secure in sub-Saharan Africa and reflecting the increase in agricultural output. While this statistic may ring hollow when millions of South Africans go to bed hungry every day, this is more a function of an income-poverty challenge rather than lack of availability due to low agricultural output, as is the case in other parts of Africa. In essence, we need to ensure that there is employment and that households have a sufficient income.

We must remember that the Global Food Security Index balances the four elements (affordability and availability, as well as quality and safety) to arrive at a rating. In this regard, South Africa produces enough food to fill the shelves of supermarkets with high-quality products but still has a long way to go in addressing household food insecurity, as many households cannot afford the necessary food to meet their nutritional demands.

Transformation

Earlier, I noted that the consensus on agricultural growth overall contrasts with the widely divergent views about the extent to which this growth is sustainable, inclusive, and transformative. It is clear that the gains we've seen in agricultural production over the past two decades have not been equitably distributed across the agricultural industry. Specifically, the growth in the agricultural sector has been largely restricted to organized commercial agriculture, sometimes at the expense of a distinct but heterogeneous cohort of farmers in South Africa.

As I argued in my book, A Country of Two Agricultures, "Nearly three decades after the dawn of democracy, South Africa has remained a country of 'two agricultures'. On the one hand, we have a subsistence, primarily non-commercial and black farming segment; on the other, we have predominantly commercial and white farmers."

The book adds: “The democratic government's corrective policies and programmes to unify the sector and build an inclusive agricultural economy have suffered failures since 1994. The private sector has also not provided many successful partnership programmes to foster the inclusion of black farmers in commercial production at scale. It is no surprise that institutions such as the National Agricultural Marketing Council estimate that black farmers account for less than 10%, on average, of commercial agricultural production in South Africa. This lackluster performance by black farmers in commercial agriculture cannot be blamed solely on historical legacies."

While this paints a bleak picture of transformation in the agricultural sector, we cannot ignore the anecdotal evidence pointing to a rise of black farmers in some corners of South Africa. We see this in field crops, horticulture, and livestock in provinces such as Free State, Western Cape, and the Eastern Cape, for instance.

Employment

Even with the adoption of technology that catalyzes agricultural productivity improvements, employment in South Africa's agriculture has remained robust. For example, there were about 922 000 people employed in South Africa's agriculture industry in 1994, according to data from Statistics South Africa. This is both seasonal and permanent labour. While the share of seasonal and regular labour changed over time, in the main, employment remained buoyant. In the third quarter of 2023, there were about 956 000 people working in primary agriculture, up 4% from 1994.

Conclusion

It is important to be mindful of the progress that has been made in boosting our agricultural fortunes (see Figure 1). In the quest to grow and be more inclusive, we should be aware of the unintended consequences of possible new policies. Equally, we must never be complacent with the dualism we continue to see in South Africa's agricultural sector.

The task, then, is how to grow South Africa's agricultural sector to make it more inclusive.

It is thus essential that both the private sector (organized agriculture groups and agribusinesses, etc.) and government craft a common vision for the sector with clear rules of engagement and monitoring systems. This can build on the work of the National Development Plan (Chapter 6 to be specific), Agriculture and Agro-processing Master Plan, Land Reform Agency (yet to be launched by the government), and other progressive programmes and policies available to the nation.

Download article

Post a commentary

This comment facility is intended for considered commentaries to stimulate substantive debate. Comments may be screened by an editor before they appear online. To comment one must be registered and logged in.

This comment facility is intended for considered commentaries to stimulate substantive debate. Comments may be screened by an editor before they appear online. Please view "Submitting a commentary" for more information.