How South Africa may leverage the BRICS chair for agribusiness

Introduction

This year South Africa assumed the role of chair of the BRICS grouping of countries, taking over from China, which chaired in 2022.[1] While South Africa previously chaired the grouping in 2018, each tenure is different and brings a new opportunity to influence the agenda within this economically influential grouping of countries. The BRICS grouping is not a formal economic or trade bloc; still the business communities from each country typically look for ways to deepen trade and investments with other BRICS partners. South Africa’s BRICS Business Council is one formation that actively engages with other BRICS member states’ business councils or chambers to explore economic opportunities within this same grouping. This year, the South African BRICS Business Council will also lead the agenda in the same form as the political principals chairing BRICS. The agriculture and agribusiness role players are appropriately represented through the agribusiness working group within the Business Council.

SA agriculture trade interests

The main interests of South African agriculture and agribusiness in the grouping are advancing agricultural exports, specifically to China and India.[2] These are countries that have relatively solid economic growth prospects and large populations, which equates to sustainable markets. Brazil tends to be a competitor with South Africa in major agricultural commodities due to its location in the southern hemisphere, while Russia is an important market for South African fruit and a major supplier of wheat. Still, since Russia invaded Ukraine, continuing commerce and creating new opportunities with the country is generally risky. With that said, the posture some businesses have taken has been to follow the national policy on matters concerning the Russia-Ukraine war.

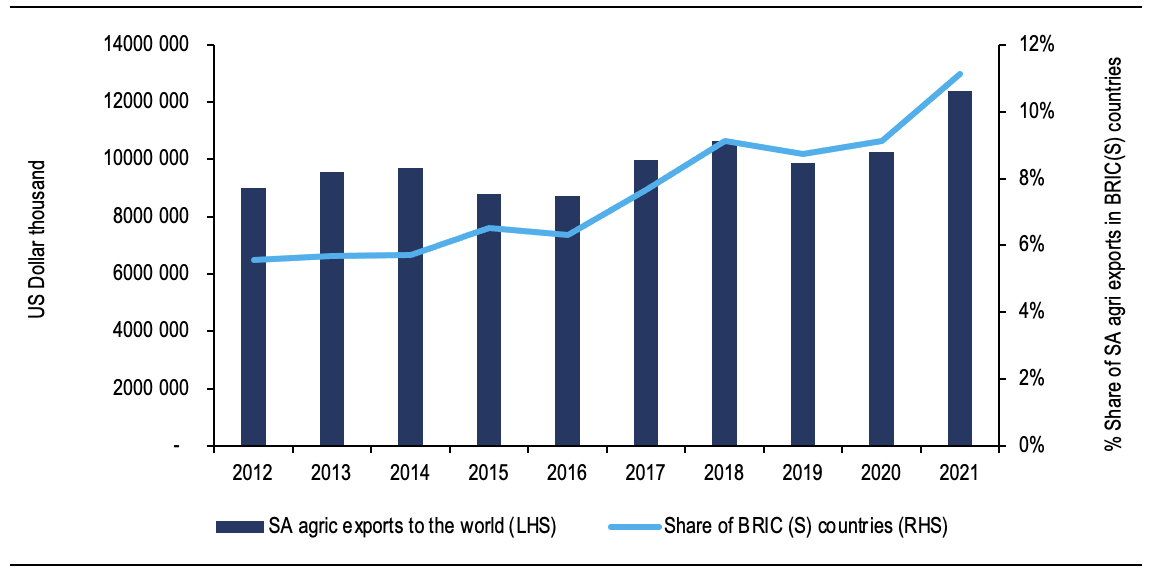

This year is another opportunity for South Africa to push for increased agricultural exports into the BRICS countries. As things stand, the BRICS countries account for a relatively small share of South Africa’s agriculture exports – an average of 8% over the past 10 years in total agricultural exports of US$9,9 billion.[3]China is the leading market, accounting for an average of 5% of South Africa’s agricultural exports to the world. The top products were wool, citrus, beef, nuts, and grapes. The second-largest market of South African agribusinesses within BRICS was Russia, accounting for an average 2% over the past decade. Citrus, apples, pears, grapes, and wine were some of the top agricultural products South Africa exported to Russia during this period. India and Brazil were negligible importers of South African agricultural products.

While the BRICS countries imported an average of US$764 million of agricultural products from South Africa, a small share in the nearly US$10 billion South Africa exported over the past decade annually, the grouping imported an average of US$196 billion worth of agricultural products from the world market. This data excludes South Africa, which provides some perspective of the overall size of the agricultural market within BRICS. The average annual figure of US$764 million the BRICS countries imported from South Africa over the past 10 years makes South Africa a small player in agricultural trade in this grouping. China is the largest importer, accounting for 67% of the total BRICS agricultural import of US$196 billion, followed by Russia (16%), India (12%), and Brazil (5%).

These realities imply that within the agribusiness stream of the BRICS Business Council and the broader political grouping, the South African representatives should continue to advocate for lowering import tariffs for agricultural products, specifically in India and China. This should take shape of commodity-specific protocol, with conducive market conditions. A reciprocity principle may be unfavourable for some South African industries. At the same time, the business community will have to actively promote the “proudly South African” agriculture (and broadly food, fibre, and beverages) products in this grouping of countries.

Regarding the import tariffs with BRICS, consider the case of the wine trade in China. The likes of Australia and Chile access the Chinese market at 0% preferential tariffs. However, South African producers face duties as high as 14%.[4] This is understandable as Australia, New Zealand, Peru, and Chile have bilateral agreements with China. South Africa does not, and thus faces higher duties. Still, the country’s involvement in BRICS, while a political grouping and not a trade bloc, should provide an opportunity to lobby for lower duties on food, fibre, and beverages products, on a commodity-specific protocol.

Such engagements, however, will not be smooth as China and India would most likely want a reciprocal engagement with South Africa. This will put South Africa in a challenging position as the country is also pushing its localization strategy, particularly in the manufacturing space, which will likely interest China and India. This is also an issue that industry players should consider when engaging with the South African authorities about their export market aspirations to China and India. So, South African policymakers will need to make necessary trade-offs, weighing both our export ambitions and the localization strategy. Trade policies and sector development strategies will need to be calibrated in ways that take advantage of new market opportunities presented by South Africa’s term of chairmanship in BRICS.

In addition to the aspect of deepening trade, other areas South African agribusinesses will most likely explore within BRICS Business Council are fertilizer trade and production, as well as deepening knowledge sharing and investment in agricultural technology and finance. It is still early in the year, and the results of these engagements will be evident towards the end of 2023.

Figure 1: South African agricultural exports and share that goes to BRIC(S) countries

Source: Trade Map and Agbiz Research

Note: We use “BRIC (S) since we did not include the South African figures in the calculations

Conclusion

Overall, BRICS involvement presents yet another opportunity for South Africa to promote its growing agricultural products and search for additional markets. Still, South Africa should not neglect its key agricultural markets, such as the African continent, EU, and some regions of Asia, which have, over the years, ensured that the country maintains sizable export value as illustrated in Figure 1. Beyond BRICS, South Africa’s priority countries for agricultural exports should be South Korea, Japan, the USA, Vietnam, Taiwan, India, Saudi Arabia, Mexico, the Philippines, and Bangladesh. All have sizeable populations and are large importers of agricultural products, specifically fruits, wine, beef, and grains.

[1]Read more at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-01-09/s-africa-to-use-brics-chair-role-to-advance-africa-interests#xj4y7vzkg

[2] Sihlobo, W. 2023. Farming in South Africa: 6 things that need urgent attention in 2023: Johannesburg: The Conversation. Available: https://theconversation.com/farming-in-south-africa-6-things-that-need-urgent-attention-in-2023-197772

[3] These calculations are based on data from Trade Map. It can be accessed at: https://www.trademap.org/Index.aspx

[4] Trade Map: https://www.trademap.org/Index.aspx

Download article

Post a commentary

This comment facility is intended for considered commentaries to stimulate substantive debate. Comments may be screened by an editor before they appear online. To comment one must be registered and logged in.

This comment facility is intended for considered commentaries to stimulate substantive debate. Comments may be screened by an editor before they appear online. Please view "Submitting a commentary" for more information.