What does Saudi Arabian membership of BRICS mean for South African agricultural exports?

Introduction

The alliance of BRICS countries has been commended for smoothening and strengthening trade among its members. Saudi Arabia’s recent membership of the alliance is a potential opportunity to expand South African livestock exports especially beef.[1] In this article we discuss how Saudi Arabia’s inclusion in BRICS could benefit the South African export of live goats, especially noting that Saudi Arabia is the largest importer of live goats. Tapping into this export market has a potential to increase communal farmers’ income and create employment, as it has done for communal wool producers.

Smallholder market access challenge

On the one hand, most goat flocks in South Africa are in the hands of communal farmers and are large enough to ensure a consistent supply of product to the market, [2] while on the other, most live goats and goat-related products are in high demand in Asia and Middle East. However, smallholder farmers still have limited or no access to these markets because of institutional and production constraints they face, such as land, water, on- and off-farm infrastructure, labour force, capital, and goods-management skills. Access to these production resources by smallholder farmers affects how they may benefit from opportunities in agricultural markets.[3]

Establishing a reliable export market could build income portfolio and livelihoods of many smallholders. Currently, smallholder goat producers derive income through the exploitation of the informal and weaker domestic market. From this income stock owners can take care of their household needs and expenses, such as paying for food and school fees.[4] Goats have other related by-products such as their skins, which can be further processed to make household furniture.[5] Live goats fetch a decent price from informal markets that could be close to one month’s pay of an old-age grant. The live-goat prices range from R1400-R2000 per goat. Depending on the number of saleable goats in a flock, a subsistence farmer can earn R150 000 per annum, most of which is profit, according to Alcock.[6] This income could be substantially increased through export markets, especially with lower or no tariffs, which is likely in trade partners with a common alliance such as BRICS.

BRICS trade partnership

The alliance of emerging economies started in 2006, when Brazil, Russia, India, and China created the ‘BRIC’ group; this was later joined by South Africa to form ‘BRICS’. The purpose of this alliance was to mobilise emerging economies and to enhance their political and economic power. In the 15th BRICS Summit, President Ramaphosa said South Africa’s trade with the BRICS member-states in 2022 had grown by 70% in half a decade. This represents an increase of more than 70% from $25 billion in 2017 to $43 billion in 2022.[7]

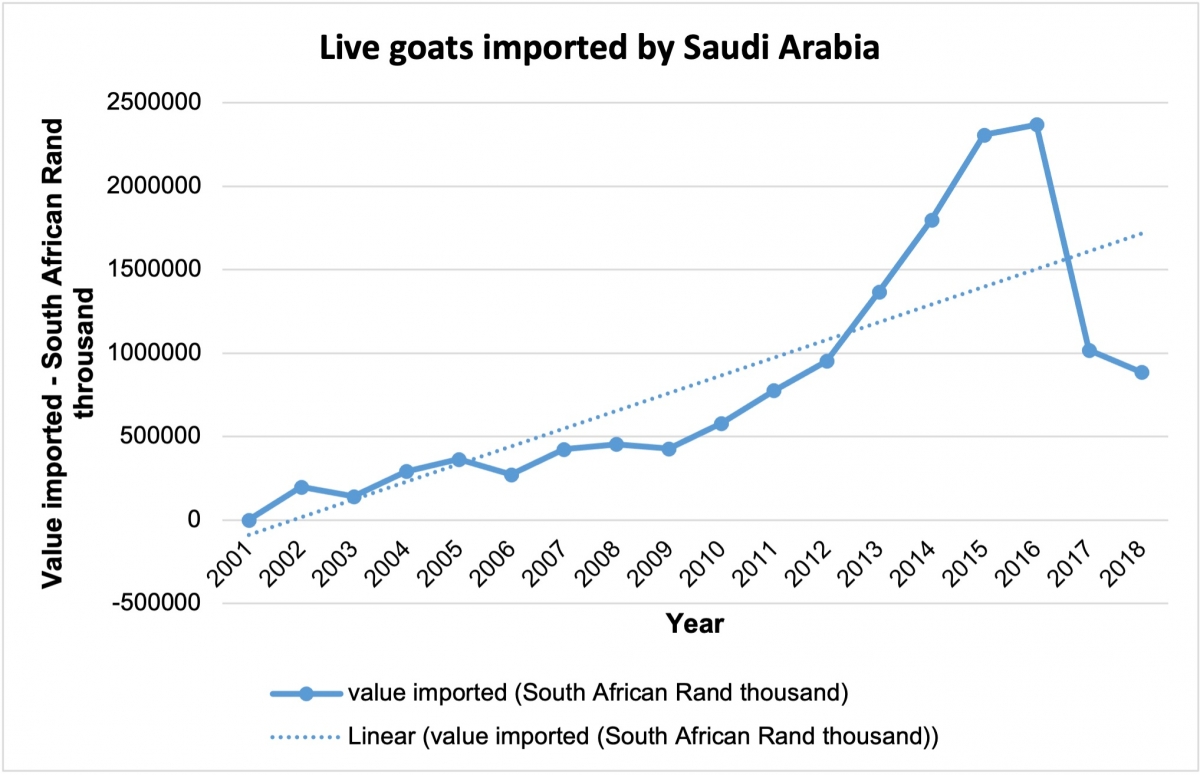

The recent joining of Saudi Arabia, which is a significant importer of agricultural products, could present an opportunity for South Africa. Saudi Arabia imported, on average, $21bn of agricultural products in the last five years, from Brazil, India, the U.S., the United Arab Emirates, Germany, France, Turkey, and Egypt . Meat and edible offal, rice, barley, milk and cream, cigars, cheese, and live sheep and goats (see Figure 1) were the most significant imports.

South Africa is a minor player in the Saudi Arabian agricultural market, accounting for less than 2% of all imports. Analysts see an opportunity to expand this market, particularly as it is a net exporter of some of the products that Saudi Arabia imports – beef, for example.[8] Another avenue could be through the export of live goats, since Saudi Arabia is the largest importer of these animals.

Figure 1

Source: Trade Map, 2024

Requirements for live animal export

In the process of exporting live goats to Saudi Arabia from South Africa, adherence to specific regulations is crucial. This has become apparent in the protests in Cape Town – and around the world - about violations of animal welfare rights in shipping of cattle to the Middle East The responsible entity overseeing these exports in South Africa is the Department of Agriculture, Land Reform, and Rural Development (DALRRD).[9] Livestock exporters must apply for an export permit from the Registrar of Animal Improvement (in Saudi Arabia) before shipments leave the exporting country. Livestock shipments must also be accompanied by country-of-origin and health certificates authenticated by the Saudi embassy in the country.

Additionally, the port of departure must be within the country of origin, passage must be directly to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and a detailed report indicating the status of animal health throughout the journey is required. Moreover, the Saudi Customs Authority requires a country-of-origin certificate to determine customs charges, waivers, or other preferential treatment for imported animals. It also ensures that products from countries banned from exporting to Saudi Arabia are not allowed entry due to human health and phytosanitary concerns.

Veterinary inspection must be conducted upon arrival at any Saudi port. If the shipment is infected with specific listed diseases, the shipment may be rejected. Quarantine may be implemented if the infection rate is below 10% whereby, on arrival, the animal will be subjected to a minimum of six days isolation in an officially approved Isolation Center and will be subjected to further tests at the discretion of the Ministry of Environment, Water and Agriculture (MEWA). Should the animal fail any of the tests, or if importers fail to comply with the conditions of import, including proper certification, it may be required to be re-exported at the owners’ expense or destroyed. However rejection of the shipment will ensue if the infection rate exceeds 10%.[10]

MEWA can ban importation from any country or area based on the health status of that region.

Discussion – a reliable export market can stimulate goat production

While initially, demand might not meet the supply as there are indications that smallholder goat producers are already struggling to meet the local demand, over time, production could be stimulated to grow significantly. Evidence from the National Wool Growers’ Association from the Eastern Cape shows that reliable markets can stimulate production.[11]

NWGA’s aim was to improve the quality of wool produced by smallholders based in the former homelands and to provide access to formal markets. Its strategy included a supply of stud rams to improve flock quality. The NWGA also provided advisory services such as training, wool sheds in villages, and assistance in linking farmers to markets. It is estimated that by 2018, stock owners’ income through NWGA had increased to R383 million, amounting to an average of R15,000 per owner.[12]

However, risks related to animal diseases, such as foot-in-mouth disease (FMD), could jeopardize expansion into this export market if they are not decisively addressed. Communal farmers are seen as the largest spreaders of FMD because there are fewer biosecurity measures taken in many communities. Furthermore, the challenge of poor infrastructure, such as roads, could make it difficult to reach some communities.

References

Beinart W. 2023. Land reform and rural production in South Africa: a pragmatic approach – STIAS public lecture. https://stias.ac.za/2022/02/land-reform-and-rural-production-in-south-africa-a-pragmatic-approach-stias-public-lecture-by-william-beinart/

Department of Land Reform and Rural Development, 2023, Guidelines for the exportation of live animals by sea, Version1. https://nahf.co.za/dalrrd-guidelines-for-the-exportation-of-live-animals-by-sea/

Khowa, A.A., Tsvuura Z., Slotow, R. & M. Kraai.2023. The utilisation of domestic goats in rural and peri‑urban areas of KwaZulu‑Natal, South Africa. Tropical Animal Health and Production, 55:204 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-023-03587-3

Marais, S. 2022. Commercialising communal goat farming in KwaZulu-Natal. Farmers Weekly,4 February.

Hussein Mousa and Alan Hallman, 2019, 'Food and Agricultural Import Regulations and Standards Report - FAIRS Export Certificate Report', GAIN Report Number SA1815, U.S. Embassy, Riyadh.

Musallimova, R. 2023. What Benefits Has BRICS Brought to South Africa? - 06.09.2023, Sputnik Africa (sputniknews.africa)

Mousa H. and Hallman A. 2019, 'Food and Agricultural Import Regulations and Standards Report - FAIRS Export Certificate Report', GAIN Report Number SA1815, U.S. Embassy, Riyadh.

Roets. M and J.F. Kirsten (2005). Commercialisation of goat production in South Africa. Small Ruminant Research, 60:187-196.

Sihlobo, W. 2024. Great news for South Africa’s beef industry. Agricultural Economics Today. 25 January.

Ntshangase, Z.M., Tafa, S., Moyo,B., Sikwela, M. & J. Van Niekerk. 2022. Factors Affecting Household Goat Farmers’ Market Participation and the Extent of Commercialization. In Goat Science - Environment, Health and Economy, Intech publishing.

[1] Sihlobo, 2024

[2] Roets & Kirsten 2005: 188

[3] Ntshangase et al.2022

[4] Khowa et al, 2023

[5] ibid

[6] Cited in Marais, 2022

[7] Musallimova 2023

[8] Sihlobo, 2024

[9] DALRRD, 2023

[10] Mousa and Hallman, 2019

[11] https://www.nwga.co.za/blog-articles/nwga/communal/studies-in-wool-communal-areas-of-eastern-capenbsp/127

[12] Beinart, 2023

Download article

Post a commentary

This comment facility is intended for considered commentaries to stimulate substantive debate. Comments may be screened by an editor before they appear online. To comment one must be registered and logged in.

This comment facility is intended for considered commentaries to stimulate substantive debate. Comments may be screened by an editor before they appear online. Please view "Submitting a commentary" for more information.