The MTBPS clears some fiscal space but it is still a path through a swamp

In the 2021 MTBPS, Treasury did an excellent job of balancing the fiscal and political pressures forced on it by the incoherence of government policy. Capital markets cheered for two reasons. First the revenue numbers were substantially better than those presented in the February budget. This created potential fiscal space of about R132 billion in the current year, and R64 and R59 billion in the next two years respectively.

Second, Finance Minister Enoch Godongwana resisted political pressure for substantial commitments to permanent increases in spending. About R60 billion (or 1% of GDP) was added to the spending ceiling in in 2021 and R30 billion over each of the next two years, less than half the value of the revenue improvement. Treasury also erred on the side of caution in projecting economic growth and tax buoyancy, which leaves substantial room for higher revenue and a lower deficit.

The increased spending path is dominated by three items: wage increases for public servants, the extension of the social relief of distress grant, and the President’s public works programme. While Treasury presented each of these as temporary, in all likelihood they amount to permanent increases in spending. Instead of conceding this reality in advance, the fiscal framework builds in large buffers of unallocated funds. By holding back part of the spending increase in reserve, Treasury deftly provided space for the political leadership to make choices and confront real trade-offs while simultaneously clarifying Treasury’s own view of the fiscal constraints within which this debate should take place.

An improved fiscal outlook that accommodates spending pressures is encouraging but there are two caveats. First, the chronic position of the country’s public finances continues to worsen. This can be seen in several metrics. Growth remains far below interest rates and GDP per capita is expected to continue stagnating. Debt service costs are crowding out social spending. Money owed by provincial governments to suppliers (largely for essential medical goods) is rising at a rapid rate. Most municipalities are in financial distress, with uncollected revenues reaching R232 billion.

The fiscal crisis of local government feeds into the bankruptcy of public utilities, and the latter shows no sign of abating. As long as Cabinet appears caught in the headlights, unable to offer a programme to overcome the grave operational and financial crises in the provision of municipal services, electricity, water, road construction, and passenger rail, declarations that “there will be no bailouts” are posturing. The ongoing destruction of value must be reflected somewhere in the national balance sheet, even if it is not recognized in the budget.

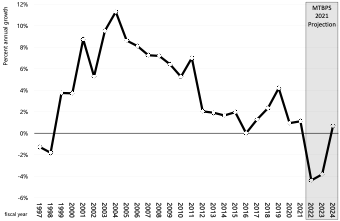

Second, Treasury’s strategy to overcome this chronic fiscal crisis rests on highly uncertain political and economic foundations. The strategy proposed is a deep shock to public expenditure executed over the next two years – 2022 to 2023. In real terms core spending is set to contract by 4 percent each year (see Figure 1) This amounts to reduction in real spending per capita of more than 10 percent. The MTBPS tells us that following this short, sharp, shock to government consumption, the period of fiscal consolidation will be concluded. Having achieved a primary surplus, the national debt will stabilize, and expenditure increases will resume along a prudent path.

Figure 1 Real growth in core spending*

Source: National Treasury, StatsSA and author’s calculations

* Core spending is main budget spending excluding interest payments, payments for financial assets and spending lines automatically funded from a dedicated revenue stream

This strategy depends on a large reduction in the real incomes of public servants and a fall in public employment. The plan to hold down pay improvements this year has not worked out. Public servants negotiated an effective increase in average pay of more than 5%, in line with inflation, and headcount numbers have surged during the Covid crisis, especially in the health sector. The idea that public servants will accept 1.5% next year and the year after might be a good negotiating tactic but weakens the credibility of the fiscal framework.

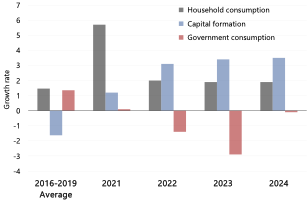

This year South Africa is recovering from the Covid shock and its economy is buoyed by a commodity boom. Aggregate spending has also grown, albeit at a very low rate. Treasury is proposing a large negative fiscal impulse in the next two years. In the forecast, a recovery in investment and sustained household demand will offset the fiscal contraction, resulting in a sustained expansion in domestic expenditure (see Figure 2).

But if the recovery in capital formation fails, or if global developments (such as deceleration in China and a tightening of global monetary policy) prove more adverse than currently assumed, the proposed fiscal shock may be held responsible for slowing growth and rising unemployment. While it is true that fiscal crisis is a headwind to economic growth, it is also true that large and sudden fiscal consolidation will also become a critical headwind to growth.

It is also the case that the shorter and deeper the contraction in spending, the more it will permanently scar public services. Public service reform is sorely needed to improve value for money, and it may well be argued that more spending won’t generate better social outcomes if the public service remains inefficient. But this says nothing about the impact of reduced spending. The last ten years of gnawing expenditure cuts show that those with organised interests in the distribution of rent through the budget – public-sector unions, business interests, and the political class – are quite capable of defending their share of the pie and passing the real costs of expenditure constraint on to the voiceless or unorganised. The temptation to engage in false economies, temporary measures, and unsustainable spending reductions will be huge over the next two years. None of this is unmanageable and in theory we might imagine a consolidation that is “growth friendly” for the public service. But neither Treasury nor any other component of government have suggested such a programme, and so it would probably be prudent to assume that it does not exist.

Figure 2 Elements of gross domestic expenditure (forecast)

Source: National Treasury (MTBPS 2021, Table 2.2) and South African Reserve Bank

The finance minister is proposing a decisive course correction in the fiscal accounts, followed by a steady course of expenditure prudence. In the context we face, it makes sense for Treasury to advance this clean and bright solution. It will help to negotiate the difficult choices government faces in the next two years. These choices include matters on which the President continues to hedge his bets for obvious political reasons – the public-sector wage agreement, the permanent extension of basic income support to working-age adults, and the resolution of the operational and financial crisis of public utilities.

The outcome is likely to be somewhere between Treasury’s negotiating position and imperatives that will define political choices, as various factions jostle for supremacy in the 2022 ANC elective conference and the 2024 general elections. The most likely long-term outlook remains a slow worsening of South Africa chronic fiscal crisis.

Download article

Post a commentary

This comment facility is intended for considered commentaries to stimulate substantive debate. Comments may be screened by an editor before they appear online. To comment one must be registered and logged in.

This comment facility is intended for considered commentaries to stimulate substantive debate. Comments may be screened by an editor before they appear online. Please view "Submitting a commentary" for more information.